The ICAA’s Documents Project at Twenty Years: From Recovery to Expansion

Arden Decker

ICAA

adecker@mfah.org

Operating for over 20 years from the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH), the International Center for the Arts of the Americas (ICAA) [Centro para las Artes de las Américas] and its landmark Documents of Latin American and Latino Art project [Documentos del Arte Latinoamericano y Latino] was established concurrently with now-renowned collections of Latin American and Latino art at the Museum. Since this time, this digital platform has served as a pioneering force in the growth and visibility of Latin American and Latino art. I currently serve as the Associate Director of the ICAA and am therefore charged with overseeing the daily needs and processes that go into the maintenance and continued growth of this initiative. This landmark anniversary invites an opportunity to reflect upon the impact of the ICAA and Documents Project on the growth and visibility of scholarship Latin American and Latinx art.

When the ICAA was established over two decades ago, the fields of Latin American and Latinx art looked different than they do today. The accelerated attention Latin American art has enjoyed via museum acquisitions, accompanying growth in the market, and the establishment of Latin American art courses at colleges and universities have increased at unprecedented rates since this time. A similar boom is now beginning to occur for Latinx art, which until recently has not benefitted from the same attention due to a lack of financial and institutional support. More universities, museums, foundations, and libraries and archives are beginning to devote substantive and significant attention and resources to art and artists from Latinx communities in the U.S. and the Latin American and Caribbean diaspora. Additionally, there now seems to be a more widespread understanding that archives and access to critical documents related to a particular artist or movement are not only of interest to specialized research communities. Thanks to the proliferation of digital platforms, an entirely new relationship is forming with Latin American and Latinx art and its audiences and also with archives and documents themselves.

In 2002, when Documents Project was initiated, there was a pressing need to address a lack in access to research, and primary sources in particular, on Latin American and Latino art. This was an issue that was urgent not just for researchers from the outside, but just as importantly if not more so, from within Latin America and Latinx communities. The mission of Documents Project can be described as a platform for providing “access to documentation in the field(s) of Latin American and Latinx art history, research, and teaching by digitizing writings by artists, leaders of artistic movements, critics, and curators from Mexico, Central and South America, the Caribbean, and the United States”.1

The ICAA was formed as part of, and in response to, a growing hemispheric swell towards the establishment and distinguishing of Latin American and Latinx art as legitimate and necessary fields of study. Since its founding, The ICAA has been one among several critical initiatives that have made substantial headway in promoting and encouraging scholarship which has also been inextricably linked to market forces and emergence of a strong base of collectors of Latin American art in particular. Our efforts have been complimented by a number of museum and university programs outside of Latin America that have worked to establish Latin American and Latino art as distinct and necessary fields of study.2

FIGURA 1. Vista de la página web del ICAA y el Proyecto Documentos (icaa.mfah.org). Julio 2022. © ICAA y Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

I am fortunate to play a central role within an institution that has undoubtedly contributed to the definition and expansion of these fields. Indeed it would be difficult, if not impossible, to measure the number of dissertations, theses, scholarly essays, articles, books, and exhibitions that have made substantial use of Documents Project in their research since the platform went public 10 years ago. But attention to documents and archives, and particularly their inner-workings, has not always been a focus of the discipline of art history nor its related institutions. This text will therefore work to highlight these aspects of the ICAA’s Documents Project, which was one of the earliest, if not the earliest, digital humanities project dedicated to increasing the visibility of Latin American and Latinx art (Fig. 1). Here, I will work to do more than simply recapitulate a historiography of the project. Rather, the aim is to make concrete the processes and research networks that comprise the Documents Project universe and to make visible the complexities of the work that goes into creation, care and maintenance of the project as it is a living entity.

I will first present an overview of the first phase of the project (2005-2015), in an attempt to clarify the ways in which Documents Project has historically functioned. I will elaborate the ways in which it has grown over time and in tandem with the building of the MFAH’s art collections. This also includes a discussion on the merits of digital collections and the challenges it presents to our particular case. I then turn to the present and future of Documents Project with a particular focus on the necessary step away from the team-based strategy deployed in the initial phase of the project and a movement towards a collaborative, partnership-based approach for the years to come. My discussion will end with the ways in which we are working to expand the footprint of both the ICAA and Documents Project beyond the online platform and into the MFAH galleries and university classrooms. Threaded through this discussion is a focus on the many individuals and institutions that have lent their expertise to this watershed initiative and the less-visible contributions they have made to ensuring that researchers continue to have meaningful engagement with the Project.

When, in 2001, the departments of Latin American Art and the ICAA were founded by Mari Carmen Ramírez and former MFAH Director, Peter C. Marzio (1943-2010) it was imperative to both visionaries that the building of a collection at the museum not only necessitated but also urgently required the establishment of a research center. At this time, even if a museum had substantive representation of these artists within their collection, little work had been done to contextualize or elevate them within the gallery walls. While a museum such as MoMA, under the leadership of Alfred Barr in the 1930s, had devoted some resources and attention to artists working south of the Río Grande, and their library and archival holdings therefore contained some related documentation, there was little attention paid to Latin American and certainly not Latinx art after the post-war period. This absence was also replicated within the discipline of art history –if museums and galleries were not displaying this art, how could art historians be expected to study it let alone incorporate the significant contributions of these artists into their teaching? If a substantive body of knowledge was not accessible in libraries or archives (which is also a pervasive problem in Latin America) how could researchers perform adequate study of these objects?

The ICAA was conceived not only as the “research branch” of the Latin American Art department, serving to support research-driven exhibitions, but also to foster new scholarship. This necessitated access to the necessary fountains of knowledge that work to contextualize, explain or even justify to unfamiliar audiences or institutional colleagues why it was necessary to include art by Latin American and Latinx artists in museum collections and in art history programs. Ramírez also consciously and deliberately took a hemispheric approach to both programs. This focus also enables researchers to take a comparative approach by placing many regions of Latin America in dialogue while also opening pathways for exploring diasporic artists and art movements as well as localized centers of production in the Latinx communities of the United States.

The reasons for establishing the ICAA were clear, but how to go about doing the hard work of creating a point of access for research and scholarship to grow from, required a well-conceived strategy for implementation. First and foremost, the ICAA purposefully does not collect physical archives and therefore may be considered as a “post-custodial”, though this term was not widely circulating at the early stages of the project.3 The decision not to collect archives was both practical and conceptual –if Documents Project was to reflect the hemispheric focus of the collection, and make an argument for the existence of vast networks of artistic development and exchange across a variety of regions and times, it would require more space than nearly any museum could afford to lend. Moreover, it was important to Ramírez and Marzio that the focus of this archival initiative be on access and that this could be achieved on a greater scale if the documents remained in their current location where in many cases physical archives were under the care of their local communities or individuals, but then shared throughout the world to anyone with a computer and internet access. It is imperative to note here that while the holdings of Documents Project are drawn from personal and institutional archives, it does not function like a traditional archive. The platform is an editorial project and one that relies on a careful formulation of criteria that materials must meet in order to inhabit its digital space and in turn become accessible to a global audience.

Phase One: Recovery

From its inception, the focus of Documents Project was placed on sourcing documents that qualify as primary sources, such as manifestos, correspondence, art criticism, lectures, unpublished manuscripts, and journal articles.4 To date, Documents Project has published over 9.000 primary sources and critical texts, which is in and of itself impressive, but I would argue what is even more surprising to the average researcher are the many hurdles and obstacles that were overcome in order to make the project viable and sustainable. The initial phase, internally referred to as “Phase One”, was aimed at recovering a critical mass of documents from across Latin America and Latinx communities in the United States. The ICAA was essentially starting from ground zero in the creation of a database –at this time, there were few repositories digitizing archival documents in a way that would have allowed for a different approach, such as aggregating data from extant repositories as is now more common. Moreover, the non-collecting, post-custodial nature of the project necessarily meant that the platform could not simply copy or replicate the holdings of an archive or library, rather, it necessitated its own conceptual framework, infrastructure, standards, and processes. As this phase has been expertly described and contextualized elsewhere, I will center this part of the discussion on a few key aspects of Phase I that point to both the challenges and the many benefits of digital archives or humanities projects.5

The fields of Latin American and Latino art history are relatively young and therefore have needed, and still need, pushes towards an establishment of best practices and support systems that many art historians may not even realize. This is one area in which Documents Project has made a significant, yet lesser-discussed contribution to the field. Something as seemingly straightforward as the creation of bibliographic records and authority control (records that standardize important data such as names, places, titles, etc.) as necessary for proper cataloguing of documents can prove challenging as the names of artist or authors may not yet have enjoyed entry into the official channels, such as the Getty’s Art and Architecture Thesaurus, an ever-evolving and entirely necessary tool utilized by librarians and archivists across the world. The ICAA is one of several projects centered on Latin American and Latino artists that actively contribute to the Getty’s thesaurus, working to provide better infrastructure that will improve the searchability and visibility of Latin American and Latinx artists in databases and repositories worldwide (Gaztambide, 2017, pp. 6-7).

It was an ambitious, yet critical, goal of Documents Project to provide access to key documents generated throughout the hemispheric Americas, but this also posed the practical questions as to how to approach the recovery and selection of documents. As there was no physical collection of documents at the ICAA or MFAH to utilize as an existing framework, a strategy for the identification and recovery of key documents was needed and given the potential impact of the project on a larger scale, the approach to this work took seriously the damaging effects of extractive, decontextualizing acquisition practices that were taking place as institutions outside of Latin America began to collect archives. As scholar and Phase One researcher Olga Herrera has explained in relation to the issues surrounding archives of Latino art:

Archives and primary documents are critical to the growth of the field, something we see reflected in the scholarship that has emerged in the last twenty plus years. However, archives are agents of power and as such are colored by the lens of those doing the collecting and management. What gets in, and what’s left out? One of the challenges is building balanced collections –ensuring that those doing the collecting are versed in and conversant with the field, and integrating the perspectives of current and future users of these materials.6

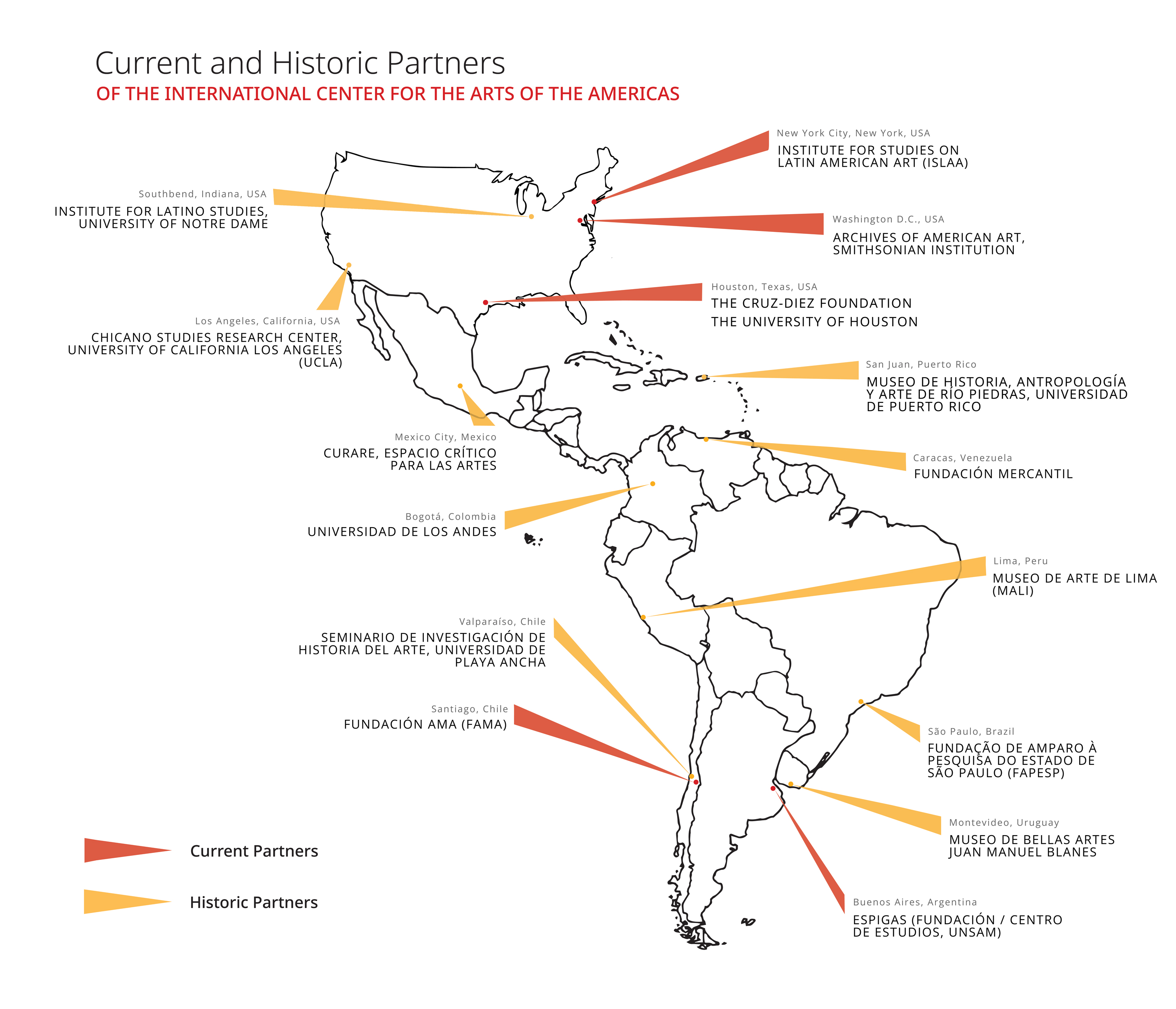

The solution to both the logistics of amassing documents and the desire to renegotiate the power structures at play with the creation of any archive was a team-based approach. At the onset of the project, 10 teams of experts in 16 cities or regions determined the selection of the most important documents from their local context following a broader editorial framework established by the ICAA (Fig. 2).7

The teams were comprised by scholars and researchers from these locations who not only best understood their own local contexts and communities but also possessed the knowledge necessary for determining which documents were most critical and merited entry into the project. This approach enabled the community of scholars from the sites of origin of the documents to be active participants in the creation of the archive without extracting documents from the roots of their origin. Yet the context of each country, region, or city posed their own set of challenges be it locating documents that might be under an artist’s bed or other less accessible locations, documents in varying states of preservation, or a lack of access to tools for digitizing these materials. Through a series of major grants from several foundations, including the Getty Foundation, Ford Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities, the ICAA provided the computers, scanners and other technical tools to the teams and secured funding for their work in the field.

FIGURA 2. Mapa de socios del ICAA en fase I y actuales. © ICAA y Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

As the scope of the project was to focus on modern and contemporary artistic production, and thereby covered the entirety of the 20th century and now the 21st, the project of recovery also necessitated a set of criteria to not only guide the research teams, but to help to ensure that meaningful connections between seemingly disparate regions or points of intersection or exchange across the hemisphere could be made. The project was therefore conceived of as both curated and editorial as a means of practicality and to ensure that the archive did more than just present a digital copy of analog materials held in repositories across the hemisphere. The development of this criteria, that served as guidelines rather than dictums, were established by an editorial advisory board that worked in the earliest years of the project to determine a set of thematic categories that could be used by the teams to facilitate their selections.

The sourcing and selection of documents posed one significant hurdle, the equally challenging was the development of the online platform for Documents Project. Firstly, this required the creation of a customized database capable of storing all of the data related to a document and in the case of Documents Project. There are plenty of archives that utilize simpler tools for the collection and management of data (such as spreadsheets and the like), but these tools are limited in their functionality for those working to catalogue and track the material. Moreover, as this was conceived at its core to be an access project, a system that would present opportunities for rich engagement of the materials was also necessary. The creation of a customized database not only allowed the ICAA team to build infrastructure for processing data, it presented the opportunity for creating systems for cross referencing documents through tagging and other associated metadata. The database also had to be capable of handling data in multiple languages (Spanish, Portuguese, and English) and no off-the-shelf platform for this existed in the early 2000s. At the inception of the initiative, no such database existed off the shelf and the ICAA therefore worked with a database and web developer in Sao Paulo Brazil, Bruno Favaretto of Base7 (now Rizoma) to create a customized platform capable of handling the needs of the project.

Each document selected for entry into the project undergoes a multi-step process before it is published on the website. After a document is selected and investigated by a researcher, it is fully digitized and made searchable via OCR conversion. A record of each document is then created in our database after which it is cataloged, which as mentioned previously, often requires the creation of new authorities and specialized knowledge of best practices. The elaborate detective work of copyrights and permissions are also cleared for each document, which is no small task in and of itself.

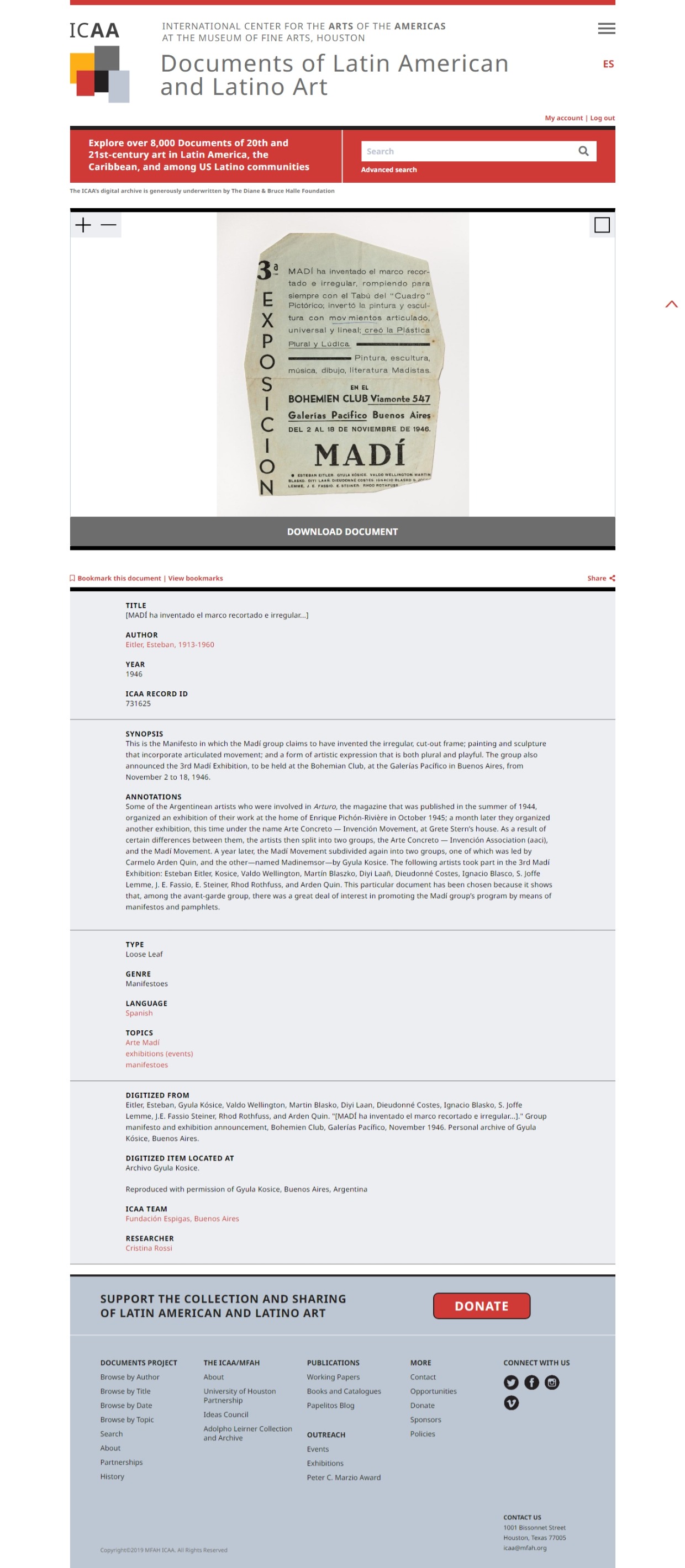

One of the distinguishing features of Documents Project from other digital archives or humanities projects is the inclusion of a synopsis and annotations or each document, which are generated by a specialist in the topic at hand. (Fig. 3) This is an extra effort that few other projects undertake, but these texts serve to describe and contextualize the document in its historical moment and also work to build meaningful connections between documents in the archive, creating a network within the archive itself. Each document entry is then thoroughly reviewed and vetted by the ICAA senior research specialist and editor are the synopsis and annotation which must also be translated into English or Spanish and then copyedited before publishing.

Facilitated by these synopses and annotations, the editorial and curated nature of this initiative is what makes the documents more accessible than an analog archival repository. If, say, a student has not yet mastered Portuguese, but is researching Lygia Clark and encounters a text written by the artist that has not yet been translated, a synopsis and annotation can give the researcher a sense of what the text is about, the key figures that are discussed, and the context in which the document was produced. The platform presents a meaningful moment of encounter for a young scholar and a starting point for deeper research may also point the researcher as the cataloguing of the documents facilitates the connection of geographically or temporally disparate artists and artistic movements.8

FIGURA 3. Vista del ICAA registro # 731625. "[MADÍ ha inventado el marco recortado e irregular...]." Manifiesto colectivo y anuncio de exposición, Bohemien Club, Galerías Pacífico, Noviembre 1946. Archivo personal de Gyula Kósice, Buenos Aires.

Additionally, these authored synopses and annotations lend visibility to the researchers that performed the hard detective work of searching for an artist’s papers that might be stored in repositories near and far and in various states of accessibility or held by an individual that disappeared from view long ago. The ICAA believes that this work should be known as it also contributes to the story a document has to tell. It also points to making evident the reasons, which can be subjective, a document was selected for inclusion. While individually authored texts require a good amount of financial support, they also work to make the ICAA’s networks visible and make clear that the Project has benefitted from a multitude of voices and perspectives that have contributed to its holdings.

Phase Two – Expansion

The second iteration of the Documents Project platform launched in April of 2020 during the earliest stages of the COVID-19 shut-down. This was yet another example of the unexpected ways in which the choice to create a digital archive, rather than a physical one, was prescient. As libraries and archives, across the world shuttered their doors to students and researchers, the press to “go digital” was all the more urgent. We witnessed the classroom move from university campus to Zoom rooms and talk of pivoting to the virtual took museums by storm as the scrambled to find ways for meaningful engagement with their publics. Suddenly, access to digital research portals was more necessary than ever.

The new website and home to Documents Project (icaa.mfah.org) was conceived not only as a visual refresh for the project but also, more importantly, as a way to increase accessibility for users and our Phase II partners. Users no longer need to be registered in order to immediately access a document in its entirety and are more easily explored thanks to the implementation of a new viewer window that allows one to zoom in on various aspects of the document. The platform is also now open access and therefore has allowed for new collaborators, such as the University of Minnesota’s recently launched Mexican American Art Since 1848 portal (rhizomes.umn.edu), to aggregate data into their own portals, thereby increasing the reach of our materials, opening us to new audiences, and creating new networks of information available on the digital sphere. It is our hope that such collaborations will continue to enrich our current holdings and encourage more research.

This launch of the second website also ushered in a new and more sustainable model for recovering documents. While the team-based approach was undeniably successful for culling enough documents to constitute an archive, it presented challenges in regards to long-term sustainability. However, it also presented the opportunity to find new paths for collaboration with both established and new partnerships with universities (the University of Houston) and institutions across Latin America and the U.S. (such as the Carlos Cruz-Diez Foundation, Fundación AMA, Fundación Gego, and most recently, the Institute for Studies on Latin American Art) who work with the ICAA to provide the resources needed for the recovery of documents. In some cases, a partner may actually hold archival materials that the ICAA is seeking while in other cases, we may look to an institution that supports research-based initiatives that are already working to promote Latin American or Latinx art. This new institutional partnership model was activated in 2018 with the Critical Documents of Chilean Art project, co-supported by Fundacion AMA a foundation in Santiago, Chile, whose mission is to increase the visibility of, and access to information about, Chilean art on a global scale. Many of the artists and cultural figures contained in this collection have not yet undergone critical study in art history inside or outside of Chile. In this case, the identification and research of these documents was performed in tandem with new scholarship being produced by the very researchers working on this project.9 While each new partnership will be tailored to the specific needs of each party, in this case, AMA supported two dedicated researchers to recover over 300 documents and to generate their synopses and annotations while the ICAA supported the processing and publication of the documents to our platform.10

This more targeted, project-based approach will also allow the ICAA to make further headway in addressing the gaps in the holdings of Document Project as we will build upon our existing collections while simultaneously working to incorporate key documents from many regions that were not covered in the first phases of the project or that do not yet enjoy substantial representation, such as the case with the fast-evolving field of Latinx art. This field has grown and changed dramatically since the first teams were operating out of the Chicano Studies Research Center, UCLA; the Institute for Latino Studies, Notre Dame, and affiliated researchers in New York, Miami, Washington D.C. and San Juan, Puerto Rico. As I write, the planning stages for this initiative, The Latinx Papers Project, are well underway and will involve a number of additional collaborations with key repositories of Latinx art across the United States.

While the ICAA and the MFAH have centered Latinx art in its initiatives since its inception, this field is growing with urgency. As mentioned in my introduction, Latinx art in the United States is undergoing critical revision and is beginning to emerge in mainstream art markets, galleries, and museums. University and college art history programs are also beginning to develop curricula that addresses the contributions of both historical and living Latinx artists. This change is in no small part due to recent social protest movements, including Black Lives Matter, that have fueled increasingly louder calls for Latinx artists to be centered in contemporary and historical narratives of “American” art.11

While there are important archival repositories across the country, primarily at universities, few have possessed the resources and infrastructure to make these materials widely accessible via digitization.12 The ICAA’s Latinx Papers project will incorporate a substantial amount of new materials into its already substantial collections in Documents Project. The initiative also presents the opportunity to redress some of the holes and gaps that were note covered in the recovery phase of the project. For example, few documents related to Texas and the Southwest region were treated by our Phase I teams dedicated to these materials. This entirely understandable given that the teams were operating outside of this particular region. However, given that the ICAA is rooted in Texas and serves a large Latinx community via both museum visitors and students at our local universities, it is now more imperative than ever to ensure that Texas-based Latinx artists feature prominently with Documents Project.13

Beyond the Desktops and Laptops: from Exhibitions to Classrooms

The expansion phase also presents new and exciting opportunities for activating Documents Project via exhibitions and educational initiatives. As mentioned, the ICAA has, since inception, provided research support for the production of exhibitions of Latin American and Latino art at the MFAH, providing its curators with research assistance and sourcing primary documents for exhibition catalogues that will also be published to Documents Project. While archival materials have frequently been presented within our exhibitions (Beatriz Gonzalez: Retrospective, Contesting Modernity, and Inverted Utopias to name a few) the role of ICAA in their selection and research was never made explicit.

.jpg)

FIGURA 4. Vista de la colección Adolpho Leirner con vitrinas de documentos del ICAA en las Galerías de Arte Latinoamericano, Edificio Kinder. Fotografía © Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

This changed with the inauguration of the MFAH’s Nancy and Rich Kinder Building in 2020. The new space provides, for the first time, permanent exhibition space for the museum’s vast collections of Modern and Contemporary Art, including a significant and prominent amount of space devoted to Latin American and Latino art. The Kinder Building also offered the opportunity for the ICAA and Documents Project to have a visible presence in the building and the chance for new audiences to be introduced to and engage with primary source documents that related directly to the works on view. By this time, Documents Project had already established a large, global network of users who are typically art historians or students of art history, but also artists, gallery dealers, auction houses and other entities that rely on this fountain of information. However, the ICAA and its contributions to exhibitions at the museum had never before been made visible to a general audience. It has also afforded us the opportunity to experiment with new ways of activating Documents Project while, hopefully, encouraging the general public to become curious about documents and better understand the ways in which research inform and illuminate museum collections.

FIGURA 5. Vista de las vitrinas de documentos del ICAA y Hirsch Library en las Galerías de Arte Latinoamericano, Edificio Kinder. Fotografía © Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

A prominent feature of the current installations in the Kinder Building is the Adolpho Leirner collection of Brazilian concrete and neo-concrete art. It was a well-publicized coup that the museum in Houston was selected to house Leirner’s unique and exceptional collection that features notorious figures –Lygia Clark, Waldemar Cordeiro, Helio Oiticica, Alfredo Volpi to name but a few– that 20 years ago were largely unknown outside of their country of origin. This collection has served as a cornerstone of the collection at the MFAH and features prominently in the inaugural exhibitions at the new Nancy and Rich Kinder Building, which for the first time offers permanent gallery space for the Museum’s collections of Modern and Contemporary art, and notably, its landmark and pioneering collections of Latin American and Latino art. Key works such as Lygia Clark’s Bicho (máquina) (1962), Waldemar Cordeiro’s Idéia Visual (1956) and Hélio Oiticica’s Vermelho cortando o branco (1958) now have a home in the galleries and can be enjoyed by audience both familiar with the artists or those encountering them for the first time.

The MFAH’s acquisition of the collection also included the Leirner library and archive that he carefully constructed and maintained as a chronicle of the works that he collected as well as documentation produced by and about the artists that worked in the collection. These resources have become essential for the curators and conservators at the museum who are charged with the display and care of the objects and provide a unique opportunity for researchers to benefit from a holistic contextualization of the artworks in the collection. Moreover, it presented the ICAA with the opportunity to create a display of important primary source materials from the Leirner library and archive in dialogue with the artworks on view. (Fig. 4) The ICAA worked with the MFAH Hirsch Library to curate a series of document displays that complement galleries devoted not only to the Leirner collection, but also Arte Madí, Joaquín Torres-García and the Taller Torres-García, as well as a purely digital display that accompanies Gyula Kosice’s Hydrospatial City (1946-1972). The document cases are filled with journals, manifestoes, exhibition pamphlets, newspaper articles and other ephemera that are made fully accessible and explorable via a series of interactive digital tablets or via mobile phone that essentially replicate the experience of researching in Documents Project for visitors to the museum (Fig. 5).14

The ICAA’s emphasis on archival research and the primacy of primary resources is also working to expose a new generation of art historians to the ways in which documents can illuminate intersections and influences not just across historical figures and movements, but to individual artworks. Discourses on intersections of archives and artistic practices are not new, nor is the use of primary sources to provide foundational research for the study of an art object. But what new narratives or lines of inquiry can be generated by documents that function as both art object and historical document? Direct encounters with analogue documents in particular can change the researcher’s relationship not only to the subject of inquiry but also to the document itself. Its materiality, the ink used, the typeset, condition of the document, its contemporary circulation and preservation history also have stories to tell. They can be lower-stake spaces for visual experimentation, stages for debate, or vehicles for collaboration not bound by distance or time.

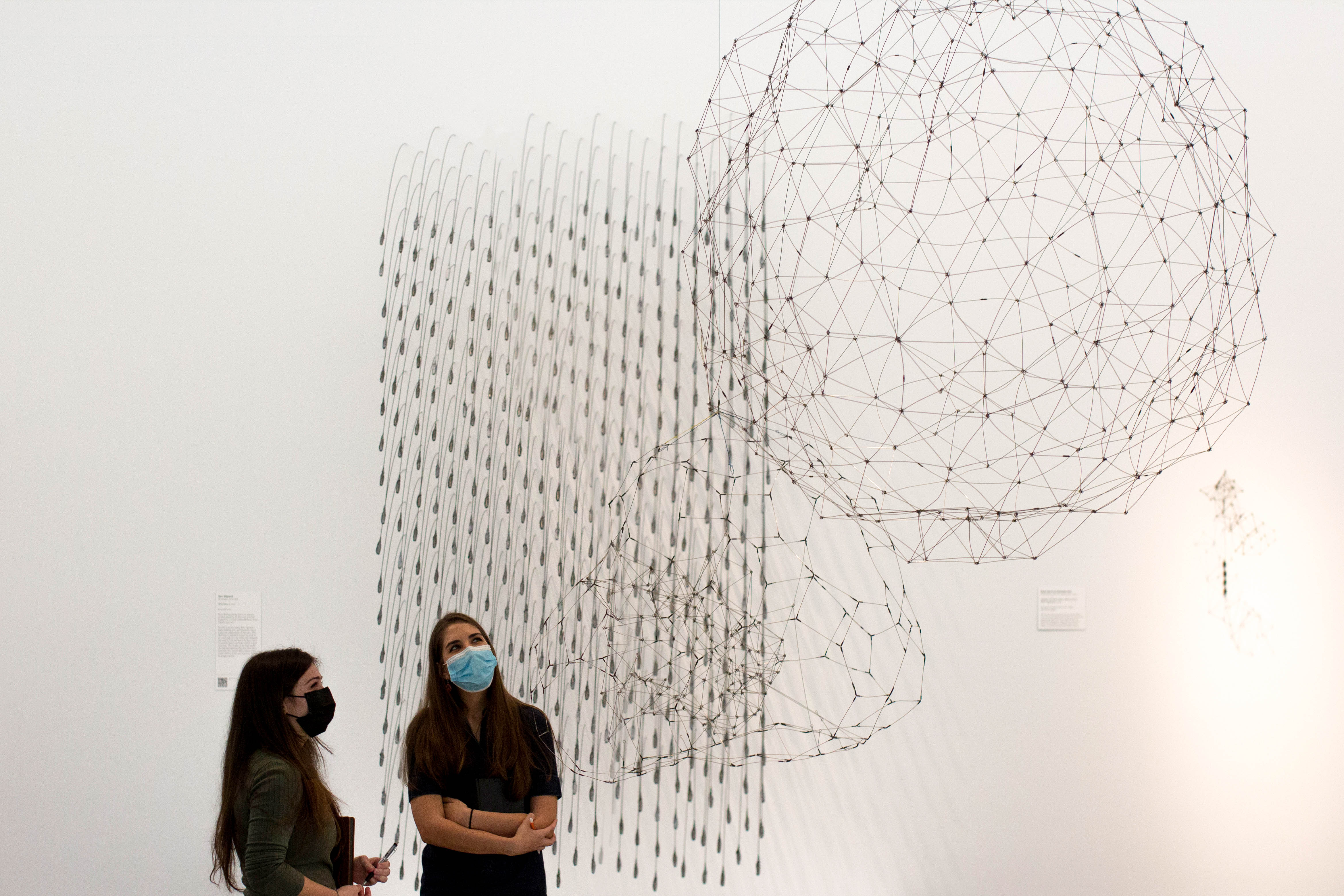

A significant advancement in this realm has been made via our partnership with the University of Houston (UH), which was formalized in 2017. One of the primary goals of our collaboration is to introduce a new generation of art historians and art students to Latin American and Latino art via direct engagement with the museum’s collections and to encourage them to develop skills for researching in libraries and archives. In 2019, the partnership instituted an annual seminar for undergraduate and graduate students studying art and art history at UH. The course utilizes Object-based Learning (OBL) as a pedagogical and methodological approach to the study of individual works in the MFAH’s collections of Latin American and Latino art (Fig. 6).15

FIGURA 6. Aprendizaje Basado en Objetos en el Museum of Fine Arts, Houston con estudiantes mirando Esfera no.8, 1977, obra de la artista Gego (Gertrud Goldschmidt), Donado por la Fundación Gego. Fotografía © Museo de Bellas Artes de Houston.

Here, I will elaborate one example from this seminar that have been particularly successful pedagogical tools in the seminar: the Adolpho Leirner collection. We have explored via the Leirner collection in the course to great success, the ways in which close study of primary sources in concert with close-looking at objects can reveal contradictions or slippages between what an artist might say they are hoping to achieve in a work of art in a written text versus what they actually do. One method we use in the seminar is asking students to closely review manifestoes and other documents produced by the artists associated with Brazilian concrete art. Within this movement, artists relied heavily on the written word to express their ideas, where they touted the use of new, industrial paints and painting techniques, a close examination of the works themselves can reveal that far older materials and applications were actually deployed in the creation of their paintings. One example that is particularly effective is that of Alfredo Volpi. The conservation scientist at the MFAH, Corina Rogge, who has studied the Leirner collection closely, leads the students through an exercise in which they learn that the artist was actually using egg tempera painting, a medium that was in circulation for centuries before Volpi’s time (Fig. 7).16

FIGURA 7. Estudiantes de la University of Houston examinando una obra de Alfredo Volpi, Bandeiras, 1960. The Adolpho Leirner Collection of Brazilian Constructive Art, compra del museo. Fotografía © Museo de Bellas Artes de Houston.

In the seminar, we also explore questions over the objecthood of a document. What can a “document-object” do that a work of art cannot? Since the advent of the avant-garde of the early 20th century, the printed word was nearly as important to artists and artistic movements as the artworks they produced. Artists books, ‘zines, and other formats that utilize paper and the document as medium further blur the line between a traditional art work and a document. As has been studied and known for many decades of art historical research, manifestos, journal articles, poetry and the like allowed artists to circulate there ideas in spaces where a work of art would be limited. Documents, not bound by the same restrictions of space or economic investment, allow ideas to maneuver in far more creative outlets and, as was the case for many –think of the advent of mail art– also allowed artists, critics, or intellectuals to practice their art more safely when working under conditions of repression or censorship. In the course, we look closely at the ICAA’s display of facsimiles we produced in conjunction with the MFAH’s Hirsch Library of examples of journals and ephemera produced by the Arte Madí movement.17 (Fig. 8) Through these examples, we demonstrate how documents also allowed artists ideas to extend beyond their immediate geographic location, allow them to connect, converge or diverge with other artists and thinkers across the world. I would argue that this is an ethos that is shared by the framework and structure of Documents Project itself.

FIGURA 8. Estudiantes de la University of Houston en la galerías del edificio Kinder investigando ejemplos de la jornada Arte Madi Universal en la colección Hirsch Library, MFAH. Fotografía © Museo de Bellas Artes de Houston.

One of the aspects of the incorporation of primary sources into undergrad and graduate art history curricula is that platforms such as Documents project allow educators who do not have ready access to archives in their home locations to incorporate documents into their work in the classrooms. Professors and educators may utilize this resource to model the ways in which primary source research not only informs the analysis and understanding of an object, but how they can bolster or defend new art historical narratives against a tried and true cannons. The revelatory nature of this for students is two-fold –they are exposed to artists, critics, and other agents of cultural production that they do not learn about in traditional art history and they begin to gain better researching skills and understanding of the tools that are available to them, be it in analogue or digital form.

Making the Invisible Visible: Documents Project in the Current Digital Landscape

When I am asked to speak about the ICAA and Documents Project for university classes or at academic conferences, I find that by the many attendees enthusiastically express how critical the platform is to their own research and teaching in classrooms, but are consistently surprised to learn about the amount of labor, specialized knowledge, and elaborate editorial framework that all serve to inform what is still considered to be a pioneering force in the development and proliferation of studies on Latin American and Latinx art. Despite the decades-long work performed by the Center and its visibility among scholars of Latin American and Latinx Art and that it serves as a critical resource for research in the field, what has been less discussed are the amount of labor and resources that are expended in the processing of each document. While the ICAA’s network of researchers is vast, the processing of documents and maintenance of the project are managed by a core team in Houston and two international colleagues. While the work they perform is essential, it is less obvious to a researcher using the site. Indeed the nitty-gritty of how modern day digital archives or collections are constructed, maintained, and made accessible have received far less attention outside of studies related to library and information sciences.

In addition to the growth in visibility of Latin American and Latinx art, a new focus on archives and the potential for digital humanities within an expanded field represent another significant alteration to the landscape of the ICAA. A bird’s eye view reveals a near explosion of archival initiatives and platforms since Documents Project first began and this has only accelerated in the last decade and the ICAA has played a large role in this growth. Many of these share in the same spirit of accessibility and expansion of research networks, which include but are far from limited to: Red conceptualismos del sur; the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art; Princeton University’s Digital Archive of Latin American and Caribbean Ephemera; the inSITE online archive; and the previously mentioned Archives of American Art, Calisphere, and Mexican American Art since 1848 (MAAS) portals. These extant platforms are now being joined by numerous other initiatives related to the digitization of museum collections of Latin American or Latino art.

Another explanation for this is the relationship to archives and contemporary art practices has long been fashionable, absorbed into the vocabulary of the contemporary art world from art practitioners to exhibitions and beyond.18 The proliferation of an aesthetics of the archive (or an archival aesthetics) serves to obfuscate or render further invisible the very real and meaningful work of the many individuals –and their respective expertise– that come together to create a collection or an archive.19 It may even be surprising even to well-seasoned researchers, who find themselves deep in the belly of an institutional archive or falling down a rabbit-hole of search terms on a digital platform, the vast network of persons and expertise that are required to not only perform the daily work of maintaining but also to activate the archival materials. The conceptual, structural, and logistical frameworks for archives and their care may be less glamourous as they are not be easily aestheticized or made fashionable, but they are nonetheless instructive and compelling to consider the ways in which different archives and archival platforms may be constructed and utilized depending upon the contents of their holdings, institution that is responsible for their maintenance, the level of support that exists (financial and otherwise), and the ways in which they might be accessed and activated.

As Documents Project continues to grow, we recognize that our work of recovery will never be fully finished or completed. However, we will continue to encourage and create pathways for new scholarship on Latin American and Latino art by making documents of Latin American and Latino art accessible. We will continue to work to bridge the gaps and center the voices of artists and cultural figures that have been ignored or understudied in art history. We will also continue to expand our partnerships and activate our network of researchers and we will continue to find ways of making the invisible work that goes into an archive more visible. It is the work of the ICAA to ensure that access to Documents Project continue to be and push further as a model for sustainable, collaborative, accessible and meaningful research now and in the years to come.

References

Alpert-Abrams, H.; Bliss, D. A. and Carbajal, I. (2019). Post-Custodial Archiving for the Collective Good: Examining Neoliberalism in US-Latin American Archival Partnerships. Journal of Critical Library and Information Sciences 2(1), 1-24. Available in: <https://journals.litwinbooks.com/index.php/jclis/article/view/87/54>.

Chatterjee, H., Hannan, L. and Thomson, L. (2015). An Introduction to Object-Based Learning and Multisensory Engagement. In H. Chatterjee and L. Hannan (Eds.), Engaging the Senses: Object-Based Learning in Higher Education (pp. 1-18). Ashgate.

Gaztambide, M. C. (2017). Sobre la contundencia del arkhé, el ICAA y el desdoblamiento del arte latinoamericano. In Archivos fuera de lugar: Circuitos expositivos, digitales y comerciales del documento (pp. 47-68). Taller de Ediciones Económicas.

González, J. A. (2018). In the Field: Latino Art Archives. Archives of American Art Journal 57(2), 57-58.

Flores Leiva, M. and Brodsky Zimmermann, V. (2021). Mujeres en las artes visuales en Chile = Women in the visual arts in Chile : 2010-2020. Ministerio de las Culturas, las Artes y el Patrimonio.

Flores, T. (2021). Latinidad is Cancelled: Confronting an Anti-Black Construct. Latin American and Latinx Visual Culture 3(3), 58-79.

Dávila, A. (2020). Introduction: Making Latinx Art. In Latinx Art: Artists, Markets, and Politics (pp. 1-21). Duke University Press.

Ura, A. (15 september 2022). Hispanic Texans may now be the state’s largest demographic group, new census data shows. Available in: <https://www.texastribune.org/2022/09/15/texas-demographics-census-2021/?utm_source=articleshare&utm_medium=social> (accessed 09/29/2022).

Ramírez, M. C. and Rogge, C. E. (2021). Looking to the Past to Paint the Future: Innovative: Anachronisms in the Work of Alfredo Volpi and Helio Oiticica”. In Z. Gilbert, P. Gottschaller, T. Learner, and A. Perchuk (Eds.), Purity Is a Myth: The Materiality of Concrete Art from Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay (pp. 147-165). Getty Research Institute.

Biografía de la autora

Arden Decker is an art historian and curator. She holds a Ph.D. in Art History from the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. In 2019, she joined the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston as the Associate Director of the International Center for the Arts of the Americas (ICAA) where she leads the Documents of Latin American and Latino Art digital archive project and other research-based initiatives.

1 ICAA, What is the ICAA Documents Project?, available in: <https://icaa.mfah.org/s/es/page/documents-project> (accessed 16/07/2022).

2 These institutions and universities include, but are not limited to, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA); the Tate; the University of Essex; Museo Reina Sofia; the Center for Latin American Visual Studies at University of Texas at Austin; the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University; the Chicano Studies Research Center, UCLA; the Institute for Latino Studies, Notre Dame University; and the Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Hunter College.

3 There are a number of excellent studies on the concept and development of post-custodial archival practices. See, for example: (Alpert-Abrams, Bliss and Carbajal, 2019).

4 Questions may arise as to why the Documents Project does not digitize and publish books and journals in their entirety. The Project does not attempt to be encyclopedic or comprehensive. Rather, it works as a point of access from which a researcher can identify and locate additional resources to support their study. Practical considerations also influence this approach. The most critical is copyright permissions, which are far more restrictive when seeking to reproduce journals or books in their entirety. However, this work may be performed in the future if resources and infrastructure provide an opportunity.

5 See: (Gaztambide, 2017).

6 (González, 2018).

7 For a full list and description of each team of researchers and partner institutions and the editorial framework in Phase One, see: <https://icaa.mfah.org/s/en/page/history>.

8 Solutions around accessibility for students has been of primary importance to the Project. This was the primary impulse for the ICAA’s multi-volume series, Critical Documents of Latin American and Latino Art. Based on the editorial framework of Phase I, that would not only collect and situate documents under a particular thematic focus, but actually fully translate documents that are selected.

9 See for example (Flores Leiva and Brodsky Zimmermann, 2021).

10 The ICAA’s chief digital cataloguer, Luz Muñoz-Rebolledo has written in detail about the case of Chile in Phase I and Phase II of the project in a two-part blog post, “Cuando el archivo se convierte electrónico”, Papelitos Blog, July 2022, <https://icaa.mfah.org/s/es/blog/post/cuando-el-archivo-se-convierte-electronico-parte-i-historia-de-la-primera-fase-del-proyecto-de-documentos and https://icaa.mfah.org/s/es/blog/post/cuando-el-archivo-se-convierte-electronico-parte-ii-metodologias-y-procesos-de-trabajo-del-proyecto>.

11 See for example, (Dávila, 2020) and (Flores, 2021).

12 One exception is the Archives of American Art (AAA) at the Smithsonian Institute (aaa.si.edu), which has a robust acquisition program dedicated to raising the profile of Latinx art, particularly under the stewardship of Josh T. Franco, the AAA’s national collector. Not only does AAA conduct an extraordinary oral history project, an invaluable resource, they are also working to digitize selections and entire collections related to Latinx art, making these critical resources available to the public. Another is Calisphere (calisphere.org), supported by the University of California system, which has made countless documents and artworks drawn from their university libraries freely available to the public.

13 In September of 2022, the U.S. Census Bureau released a report in that indicates that the number of Latinx [officially categorized as Hispanic] residents may now exceed the number of white residents in the state’s population. See: (Ura, 2022).

14 The ICAA’s interactive digital platform for the Kinder Building may be accessed here: <https://icaamobile.mfah.yourcultureconnect.com/>.

15 For an introduction to Object-Based Learning as a pedagogical tool, see (Chatterjee, Hannan and Thomson, 2015).

16 The collaboration between curators and conservators in the study of works from the Leirner collection have resulted in new scholarship on Brazilian concrete and neo-concrete art. See, for example: (Ramírez and Rogge, 2021).

17 The Hirsch Library maintains and active and robust acquisition program in the areas of Latin American and Latinx art and their collaboration with ICAA was critical to the installations in the Kinder Building. See: Katie Bogan and Sarah Stanhope, “ICAA-Hirsch Library Facsimile Project: Latin American Rare Books, Periodicals, and Ephemera in the Nancy and Rich Kinder Building”, Papelitos Blog, accessed July 27, 2022, <https://icaa.mfah.org/s/es/blog/post/icaa-hirsch-library-facsimile-project-latin-american-rare-books-periodicals-and-ephemera-in-the-richard-and-nancy-kinder-building>.

18 The concept of an “Archive Fever” first introduced by Derrida in 1995, was quickly followed by exhibitions and studies, such as Ingrid Schaffner’s Deep Storage (1998); Okwui Enwezor’s Archive Fever (2008); Hal Foster’s “An archival impulse” (2004) and Simone Osthoff’s Performing the Archive (2009), to name a few, all pointed to a turn towards the archive as framework and material in the work of a multitude of contemporary art practitioners.

19 It should be noted that this is not the case for studies emanating from the fields of Library and Informational Sciences where one may find a wealth of sources that illuminate the inner-workings and technical aspects of archival practices. Rather, it is the field of art history that has worked to develop theories on the archival that often ignore these seemingly mundane concerns that treat the archive as an aesthetic or medium.